Category: Team Organization

-

Bias in interviews and why hiring in product is broken

Hiring in product is broken, and those hypothetical product questions you get asked in interviews are just the tip of the iceberg. “Describe a coffee cup.” No, you’re not in the middle of a therapy session, you’re in a product manager interview, and a bad one at that. If you can, you should get up…

-

What do you do when product and customer success won’t play nice?

Too often, customer success and product teams treat each other like adversaries. Here’s how to fix that. What kind of relationship do you have with your company’s customer success team? I often ask product teams this question, and the answer is usually that there isn’t a relationship at all. And if there is, it’s hanging…

-

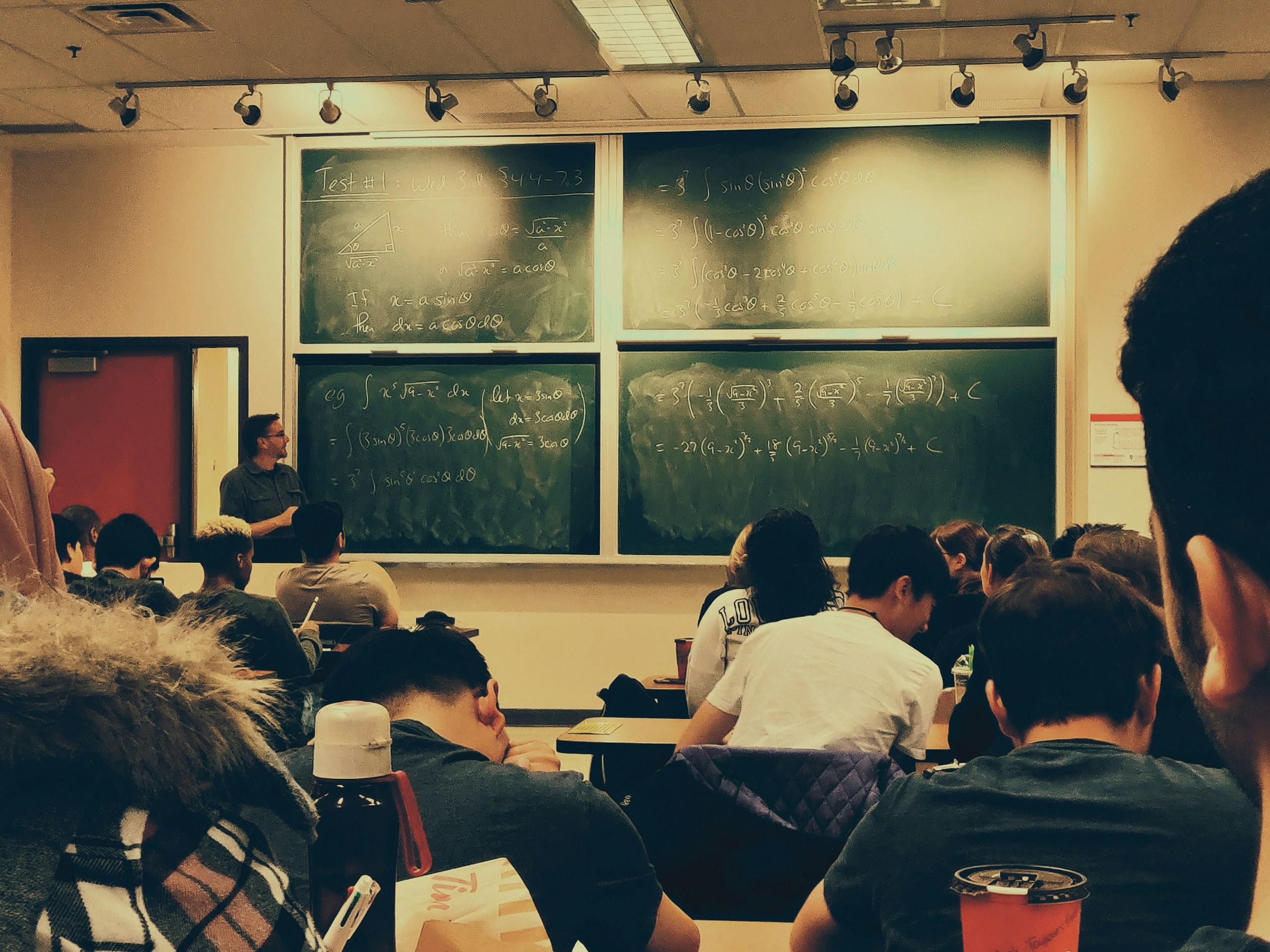

Can common challenges in project management be solved through calculus?

Because the world moves so fast, product management is seldom a linear process. We can’t afford to let our thought processes be linear, either. Welcome to product calculus. Think back to your school days, and specifically math class. As you moved past arithmetic, you probably started your journey into advanced mathematics with algebra. As you…

-

Transparency in the workplace: effective teams don’t keep secrets

There’s a difference between privacy, which is based on trust, and secrecy, which isn’t. To maximize your team’s potential, you need to foster privacy and eschew secrecy. Our mental spaces are fascinating. Sometimes, we may keep certain information to ourselves because we know that we’re trusted to complete a task. We don’t need to involve anyone…

-

Use a premortem to predict the future

What if there were a way to figure out the problems that a project would encounter before you started work on it? With a premortem, you can do just that. If there is one constant we can count on, it’s that mistakes will happen. When we start a new project, though, that can be the…

-

Should you hire a technical pm?

“We need to hire a technical PM.” I’m going to share a harsh truth here. No, you don’t. You need an architect, a project manager, or any number of jobs that directly speak to the problem you are facing. Your issue is that you haven’t defined that problem, and are more than likely listening to outside…

-

Don’t let ego-driven development drive your product creation

An ego-driven development process is a recipe for failure. Make sure your focus is on the customers and not yourself. Too many times I’ve heard this: “I know what the customer wants.” Immediately, my brow furrows a bit, as I press for more answers. Usually, at this point, I ask, “How do you know?” What happens…

-

How to onboard a product manager

So, you’ve made the hire. Congratulations — finding the right product manager who can help your team succeed is a huge burden off your shoulders. As a member of the welcoming committee, you well know that onboarding is extremely important to the success of your new colleague. Here are the stakes, according to Harvard Business Review (HBR):…

-

What exactly is a “full-stack product manager?”

What is a full-stack product manager? Well, I think we should start by breaking down both terms. Full-stack, in the tech sense, describes someone who is a jack-of-all-trades, but (generally) a master of none. You usually see this term on engineering teams, where job descriptions ask for “full-stack” candidates by requiring skills that are critical for…

-

Building a better relationship between customer success and product

If I asked you about your relationship with your customer success team, what would you say? Whenever I ask product teams this question, I’m generally surprised by the answer: that there isn’t one. And if there is, it’s barely hanging on. Often, the relationship is very back and forth, with CS handing off customer problems…

-

[Lean] Building an internal growth process for your teams

Use these two tools to Lean on learning to get your teams ready to execute better each time they work I’ve seen my fair share of companies. As a former director of strategy for the incubator Cofound Harlem and a product strategist for the agency Philosophie, I’ve had the experience of keeping track of the…

![[Lean] Building an internal growth process for your teams](https://images.unsplash.com/photo-1536392706976-e486e2ba97af?ixid=M3wzOTM3OTV8MHwxfGFsbHx8fHx8fHx8fDE2OTc4NjUwNDJ8&ixlib=rb-4.0.3&fm=jpg&q=85&fit=crop&w=2560&h=1707)